The event of a great flood engulfing the Earth around 11,600 BC, as told in Mexica-Nahuatl mythology, offers an intriguing entry point into the complex and diverse web of flood myths found across many cultures around the world. In Mexica-Nahuatl mythology, this event is part of their cosmic and historical understanding of the world, symbolizing the cyclical destruction and rebirth that is central to their worldview. The idea of a great flood is far from unique to the Mexica (commonly known as the Aztecs); similar stories exist in Sumerian, Hebrew, Greek, and Hindu traditions, among others. This universal flood narrative speaks to both mythological and perhaps geological or climatic realities of our distant past.

The Flood in Mexica-Nahuatl Mythology

In the Mexica worldview, time and existence are cyclical. The universe passes through multiple cosmic ages, known as "Suns," each ending in a cataclysmic event that brings about the destruction of the current world and the birth of a new one. According to the Nahuatl-speaking Mexica people, we live in the Fifth Sun, which followed four earlier cosmic epochs, each ending in a catastrophe. The flood that occurred around 11,600 BC is linked to the end of the Fourth Sun.

The Fourth Sun, known as the Sun of Water, was ruled by the god Chalchiuhtlicue, the goddess of water, rivers, seas, and storms. It was during this era that a great flood engulfed the Earth, destroying much of what existed in preparation for the emergence of the Fifth Sun. According to this mythology, humans were transformed into fish to survive this aquatic apocalypse. This flood narrative, while mythological, reflects deep cultural anxieties about natural disasters and the uncontrollable power of nature.

Similarities with Other Flood Myths

The Mexica-Nahuatl flood myth bears striking similarities to other ancient flood stories. For example, the biblical story of Noah’s Ark, where God floods the Earth to cleanse it of sin, has parallels to this mythological cycle of destruction and rebirth. In both stories, a deluge wipes away the old world, allowing for the creation of a new one. Similarly, the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh recounts the tale of Utnapishtim, a man who builds a boat to survive a great flood sent by the gods.

These shared themes suggest that the flood myth may have a common origin or reflect widespread experiences of natural catastrophes that ancient peoples interpreted through the lens of their spiritual beliefs. The timing of these myths, often correlated to the end of the last Ice Age, invites speculation that they may have been inspired by real geological events, such as glacial melting, rising sea levels, or regional floods that devastated early human settlements.

Geological and Climatic Context: The End of the Ice Age

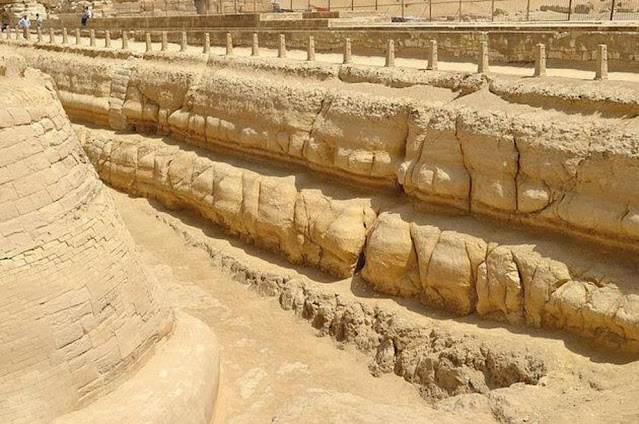

If we step outside the mythological framework and consider the geological context of 11,600 BC, we find that this period coincides with the end of the last Ice Age. Known as the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, this was a time of significant climatic change. The Earth was warming, glaciers were retreating, and sea levels were rising. This dramatic environmental shift would have profoundly impacted early human societies. Coastal areas, which were home to many early civilizations, would have been submerged by rising seas, while the increased frequency of storms and floods would have further destabilized human populations.

The melting of the glaciers and the release of massive amounts of water could have led to localized or even regional flooding on a scale that would be remembered in myth. The Mediterranean, the Black Sea, and other bodies of water in the Near East and Central America could have expanded rapidly, giving rise to the great flood stories that became integral to the spiritual and cultural narratives of these ancient civilizations. The coincidence between the timing of these floods and the mythology of the Mexica and other cultures is too striking to ignore.

Symbolism of Water and Floods

In many ancient cultures, water holds a dual symbolism: it is both life-giving and destructive. This ambivalence is reflected in the Mexica flood myth. Water is necessary for sustaining life—rivers and lakes provide nourishment, and the rains are crucial for crops. However, in excess, water becomes a destructive force, obliterating civilizations. In the Mexica tradition, this destructive capacity is embodied in the goddess Chalchiuhtlicue, who not only nurtures but also unleashes the flood that destroys the world of the Fourth Sun.

The notion of water as both a purifier and a destroyer runs through many flood myths. The biblical flood purges the Earth of wickedness, while the Sumerian flood in the Epic of Gilgamesh is sent by the gods to control overpopulation. In the Mexica myth, the flood signifies the end of a cosmic cycle and the preparation for the new order of the Fifth Sun. This dual symbolism points to a deep understanding of nature’s power and the precariousness of human life in the face of natural forces.

The Role of the Gods in Mexica-Nahuatl Mythology

In Mexica cosmology, the gods play a central role in shaping the fate of humanity. The flood is not a random event but an expression of divine will. The gods of the Mexica pantheon, particularly Chalchiuhtlicue and Tlaloc (the god of rain), control the waters, determining when they will nurture and when they will destroy. This reflects the Mexica belief that their existence was contingent on maintaining balance and harmony with the natural and divine forces of the universe.

The flood myth also highlights the Mexica understanding of time as cyclical rather than linear. Unlike in the biblical tradition, where the flood is a one-time event, the Mexica flood is just one in a series of cataclysms that mark the transition between cosmic ages. This worldview emphasizes the impermanence of human achievement and the inevitability of destruction and renewal. For the Mexica, the flood was both an end and a beginning, a way of cleansing the world in preparation for a new era.

Mythological and Historical Resonance

Although the Mexica flood myth is rooted in their own cultural and religious traditions, its themes resonate beyond the boundaries of Mesoamerica. Flood myths from other parts of the world reflect similar concerns about the relationship between humanity and nature, the role of the gods in determining human fate, and the fragility of human existence. These myths also reveal a shared human experience of living in a world that is subject to unpredictable natural forces.

The timing of the Mexica flood myth, around 11,600 BC, is particularly interesting because it corresponds to a period of significant climatic change. The end of the last Ice Age would have been a time of upheaval for early human societies, as rising sea levels and changing weather patterns disrupted traditional ways of life. These events likely left a deep impression on the collective memory of early civilizations, giving rise to flood myths that encoded both the trauma of these experiences and a hope for renewal.

The Universal Flood Archetype

The Mexica flood myth can be seen as part of a broader, universal archetype that appears in cultures across the world. Carl Jung, the Swiss psychoanalyst, identified flood myths as expressions of a deep, collective unconscious that reflects shared human concerns about survival, renewal, and the relationship between humanity and the divine. The flood archetype symbolizes the potential for destruction and the promise of rebirth, a theme that is relevant not only to ancient peoples but also to modern societies facing ecological crises and natural disasters.

In this sense, the Mexica flood myth continues to resonate today, offering a reminder of the power of nature and the cyclical nature of life. Whether viewed through the lens of mythology, geology, or psychology, the flood story speaks to the human condition: our vulnerability to the forces of nature, our desire for renewal, and our belief in a higher power that controls the fate of the world.

The Mexica-Nahuatl myth of a great flood around 11,600 BC reflects the rich symbolic and spiritual traditions of Mesoamerican peoples. This story is part of a larger tradition of flood myths found in many cultures, from the Sumerians to the Hebrews to the Greeks. These myths offer insights into how ancient peoples understood their place in the universe, their relationship with the gods, and their vulnerability to natural forces. The flood myth is also a reminder of the cyclical nature of existence, a theme that continues to resonate in modern times as we grapple with our own environmental challenges and uncertainties about the future. Whether viewed as a spiritual parable or a reflection of ancient geological events, the flood myth offers a powerful metaphor for the enduring tension between destruction and renewal.

No comments:

Post a Comment